Ekkehard Jost

INSTANT COMPOSING AS BODY LANGUAGE*

* The title derives from an interview with Cecil Taylor

in Wire Magazine 46/47 (December 1987).

Towards an Understanding of Cecil Taylor's Music of the Last Twenty Years

Starting where we left off...

In the late sixties, while working on my book Free Jazz, as I started for the first time to put into writing my thoughts about Cecil Taylor's approach to playing, perceived then and now as somehow difficult, unruly and at the same time exciting, I tried to find analytical categories that would allow one to get beyond mere subjective description.

In the meantime, I've had the opportunity on several occasions to experience Cecil Taylor in person - after a performance at New York's "La Mama Annex," when I tried to discuss his music with him, he wished only to talk about Black Dance, something I knew nothing about. Then: concerts and appearances at festivals at such diverse places as the Philharmonie in Berlin, on the lawn at Moers, in Chicago at the "Jazz Showcase"; there the club manager, Joe Segal, had on the previous evening promoted Taylor's performance by remarking, with singular narrow-mindedness, that anybody who wanted to see a beautiful Steinway get demolished should by all means drop around.

Starting where we left off...

The ambivalence I've felt towards Taylor's music since the very beginning I still feel today. A poor qualification for writing liner notes, from which one normally requires the unconditioned praise of an apologia? If so, then so be it: with Taylor there are always going to be two sides to every argument. Still, ambivalence is not to be confused with indifference.

Starting where we left off...

Did Conquistador and Unit Structures really hold what they promised twenty years ago? At that time, I saw those records as a path-breaking first step towards a form of free jazz in which "spontaneity and constructivism need not be mutually exclusive", and whose "freedom... does not mean the complete abstention from every kind of musical organisation, [but] lies, first and foremost, in the opportunity to make a conscious choice from boundless material... [and in shaping] this material in such a way that the end result is not only a psychogram of the musicians involved, but a musical structure, balancing in equal measure emotion and intellect, energy and form." 1)

In the meantime it has become clear that Cecil Taylor has been truer to himself and to his musical path than hardly any of his fellow combatants in that October Revolution of jazz. With Taylor there were no excursions into the more profitable idioms of Rock/Funk/Punk, no back-to-the-roots of jazz tradition, the invoking of which has so often only signified musical regression; there has been no move towards electrification, no digitalisation, no picturesque exoticism. What has thoroughly changed is Taylor's approach to performance; it has become more theatrical, accompanied by song and dance. But even this doesn't signify an altering of basic values - dance and theatre have always greatly appealed to Taylor. Their inclusion into his appearances thus represents nothing more than his having prevailed over the restrictive conventions of normal concert routine (enter / sit down / play / stand up / bow / exit).

Biographical Sketch

Well into the sixties, Cecil Taylor's biography is marked by a struggle to meet basic existential needs. Engagements are rare and seldom proceed under acceptable conditions. Now and again there are possibilities for recording, but even these are hardly suited to assure survival. "I've had to simulate the working jazzman's progress. I've had to create situations of growth - or rather, situations were created by the way in which I live," said Taylor in a 1965 interview with Nat Hentoff. 2) Only at the beginning of the seventies do circumstances gradually begin to improve for Taylor. In February 1970 he is appointed to the faculty at the University of Wisconsin, where he gives workshops on "Black Music from 1920 to 1970." The years 1972-73 he passes with Jimmy Lyons and Andrew Cyrille as "Artists in Residence" at Antioch College. In 1973 Taylor receives a Guggenheim Fellowship and in 1977 an honorary doctorate from New England Conservatory in Boston, where he had once studied. His European tours evolve into his major source of subsistence. Taylor: "..during the mid-'70s we were doing 10 or 12 concerts per tour, and no of the attendance totals were under 2,000. Then we come back to read the trade papers and man big in the business saying, 'Well, we cannot present that kind of music on television because the audience will not accept it'." 3) As late as 1984 Taylor declares: "..when we were in Europe in March, and had all these concerts, it was kind of difficult for us to return to New York City, because there simply was nothing, absolutely nothing. I couldn't even tell you why. This is strange because Americans always conceive of themselves as having outgrown Europe." 4)

Cecil Taylor plays in Europe as soloist with his Unit at all significant festivals; most of his records are also recorded in Europe, for French, Swiss, or West German labels like Shandar, Hat Hut MPS and Enja.

Paralleling his growing international renown and economic success is an expansion of Taylor's. artistic perspective. From the very beginning he has been interested in ballet, and now begins to work with dancers; he receives commissions from Alvin Ailey's Harlem Dance Company and from Mikhail Baryshnikov. In Japan, he absorbs impressions from the Kabuki theatre, a centuries-old blending of drama, poetry, dance and music; this influence is felt in a new sense of gesture and sonority, as well as in the increasingly important role assigned to ritual.

Supplementing his work as a soloist and with the Unit, a number of sensation-stirring collaborations materialize for Taylor: in 1976 he performs with the pianist Friedrich Gulda in the Austrian village of Moosham, and in 1977 he shares the stage of New York's Carnegie Hall with the pianist Mary Lou Williams, an event riddled with misunderstanding; the results of this concert are released. as a double-LP under the misleading title Embraced. An encounter with Max Roach in 1979 (LP Historic Concerts) proves, by contrast, substantially more fruitful; the result here is a music rich in interaction, stamped with rhythmic and tonal variety.

Yearly concert tours, the presence on countless festivals, commissions for new compositions, invitations to lead workshops and orchestral projects, plus a series of successful recordings - all of this enhances Taylor's reputation as a seminal force in contemporary jazz; international recognition begins to translate into a half-way decent degree of economic security, the most visible sign of which is a brownstone house in Brooklyn Taylor purchases in the early 80's. Abandoning the Lower East Side after having lived there for the previous two decades, he makes this his permanent residence and place of work.

When Gudrun Endress asks him if he had always earned his living through music, he answers: "It always worked out somehow. The question is: how many houses can you live in at the same time? How many cars can you drive at the same time? How many swimming pools can you swim in at the same time? On the other hand, I can be reading in ten books at the same time..I'd like to emphasise once again: I feel a lot more joy now; most of all I enjoy myself when I'm playing, and sometimes I'll catch myself thinking: My God! Ten years ago you couldn't have played like that." 5)

Solo

The superlatives conferred on Cecil Taylor by jazz publicists reduce again and again to the same clichés: the most percussive of all pianists (plays with Max Roach, the most melodic of drummers), the intensest, the most orchestral, the most radical, the most experimentalistic, the most uncompromising and so forth...Quite a bit of this is probably true; much is simply irrelevant or misleading; very little is helpful.

The frequently expressed assertion, for example, that Taylor is the most percussive pianist of all times, overlooks not only the extremely percussive approach of such stylistically different pianists as Morton, Monk, and Silver, but also creates the impression that the percussive element in Taylor's playing is the most central, which is in no way the case. 6) Another opinion, that the rudiments of Taylor's pianism find their "purest" expression in his solo recordings, also leads one astray: in actuality, Taylor's solo work follows a different set of rules than those of his work with the ensemble, and as a consequence has its own contour and personality. In principle, both his activities as soloist and those as band member and leader of the various Units are equally important - each inspires the other. They do ultimately represent, however, two clearly separable spheres of musical creativity, and it therefore seems advisable in what follows to discuss each in a separate section.

Eight LP's, recorded between 1968 and 1986, document Cecil Taylor's solo work to date; a further solo performance occupies one side of a Unit LP (Spring of 2 Blue Js). Here is a chronological listing: Praxis (Italy 7/1968), Indent (Yellow Springs 3/73), Solos (Tokyo 5/73), Spring of 2 Blue Js (New York 11/73), Silent Tongues (Montreux 7/74), Air Above Mountains (Austria 8/76), Fly Fly Fly (Villingen 9/80; this was unfortunately not obtainable), Garden (Basel 11/81 ) and For Olim (Berlin 4/86). All of these arose from live performances; it appears that Taylor consciously eschews recording studios.

Technique

For the unprepared listener, after having once recovered from the initial shock, the easiest point of entry into Taylor's music is doubtlessly his breath-taking virtuosity. Long before one begins to hear and appreciate the unique structural features, the rhythmic and tonal connections, and the formal processes in Taylor's music, one cannot help being impressed by his heightened manual artistry and technical competence. But Taylor's pianism involves much more than just the stunning ability, so readily demonstrated, to play fast. At least as important as that frenzied interlocking of motifs and those cascades of clusters, is the clarity with which all this is achieved - it's not as though Taylor, quasi delirious, sweeps over the keyboard, muddying the contours with too much pedal. On the contrary, what lifts Taylor's playing beyond mere technical dazzle is not speed alone, but rather the compounding of speed, density, and the precise articulation of every single detail. For Taylor, precision signifies more than just an incidental aspect of instrumental technique - it is an essential component of his aesthetic: "....first of all I want clarity of sound, I want the precision of the note as it is struck... Playing Bach, for instance, when I was eight or nine, it became very clear that each note was a continent, a world in itself, and it deserved to be treated as that. When I practise my own technical exercises, each note is struck, and I hear it, and it must be done with the full momentum and amplitude of the finger being raised and striking - it must be heard in the most absolute sense." 7)

Along with this insistence on articulative clarity, already evident in his earlier recordings, Taylor develops over the years a finely differentiated approach to touch-technique; the main point of this is no longer mere clarity of tone-production for single notes, chords and clusters, but rather to deepen his influence over sonority itself, its rise and decay, its resonances bound to a specific instrument. In contrast to other pianists considered part of the jazz avant-garde, Taylor generally abstains from playing inside the piano, as well as preparing the strings. Instead, he begins to employ the sostenuto pedal, a device understandably banned in the body of his work; he uses it sparsely and with purpose. One instructive example is the LP Garden, where the pedal helps produce diffuse masses of sound as a foil to the clear linearity of the section that follows; another is For Olim, where this time all three pedals serve important tone-colouristic and articulative functions. In other contexts, Taylor achieves such nuances by touch alone. Touch of course has many facets: how he strikes the keys with his fingers, how he times the release of force, how he balances tension and relaxation; the wrists and arms are also involved - indeed, the entire body participates in the process.

The precise articulation of each musical event, along with a marked tendency towards staccato playing has probably contributed to Taylor's image as jazz's most percussive pianist. One could however with equal justification (and similar paucity of meaning), characterize him as the most pianistic of pianists. Certainly there is one dimension to his playing that is primarily percussive, and therefore not related to classical techniques. I'm referring to his cluster technique, whose application includes everything from the forceful use of palms, elbows and forearms, all the way to a kind of virtuosic "drumming" procedure; this involves Taylor stiffening his fingers to utter rigidity; then, the two hands, generally held close together, alternate in an immensely fast tremolo movement, scampering over the keyboard, as if in chase; the result is an onslaught of more or less wide-spanned bands of clusters. Without doubt, this type of tone-production is percussive; but it's percussive with a degree of perfection that would make many a master drummer blush with envy. And also in this case Taylor's percussiveness serves primarily as a means to a normally non-percussive goal - the creation not of rhythm, but of a liquid and flowing sonority.

The fundamental importance Cecil Taylor attaches to sound, to the clarity of attack, and with it, to the conditions for tone-production, determine his relationship to the instruments with which he works, or, perhaps more accurately: to the instruments with which he is forced to work. Naturally every pianist prefers to perform on a good instrument. However, for Taylor, the type and quality of his instrument is an essential component of his technique; it comprises, along with the technique itself, a cornerstone of his musical message. Until relatively recently, Taylor had to make do with whatever he found standing on stage. This of course is the usual situation in the jazz scene, and one need not delve nearly as far back as to the old live recordings made at the "Café Montmartre" in Copenhagen in 1962 to understand how very much a barroom upright limits the range of musical expression. Even in the later solo LP, Praxis, recorded in Italy (1968), it is easy to understand how damaging an inappropriate instrument can be for Taylor's music. Not before the mid-70's, as a consequence of his growing international reputation, has Taylor been in a position to command his instrument of choice, and this has occurred mainly in Europe; among classical pianists, this is a privilege granted to every even moderately well-known artist. Taylor's preferred piano is the large "Bösendorfer Imperial" grand, and this is by no means an accident: the instrument is very rich in overtones, yet has a clear tone. It also has available in its bass register nine extra pitches leading down to the contrabass C, which Taylor puts to exceptionally good use (as can be heard on For Olim). A further virtue of the Bösendorfer is its comparatively stiff action; this presents to the player a resistance Taylor values high: ".. [It] will stop you cold if you're not ready." 8)

Stylistic features

Instrumental technique for its own sake is sterile and empty. It acquires substance only when employed as a means of assisting musical expression; its purpose is to help an artist get across his or her ideas (or someone else's) to an audience; it also helps musicians to communicate freely with one another ... to make music.

Sometimes it seems that Cecil Taylor's enormous technical brilliance hampers access to his music. He plays with great virtuosity, speed, precision, and with a breath-taking ability to keep going; but what is he actually playing?

Cecil Taylor's music has remained quite true to itself over the years, and still it has undergone a number of transformations. As starting points for our discussion of its stylistic features, let us consider four items: rhythm, tonality, texture, and large-scale formal organization. To maintain that Taylor's solo music is rhythmically and tonally free is to say practically nothing, for the music is in its own terms highly structured. In 1975, I identified the essential rhythmic component in Taylor's music as energy, a concept whose metaphoric virtues are admittedly not unproblematic. In any event, energy, as I am using the term, has nothing to do with loudness measured in decibels; it is, however, quite clearly a variable of time; further, it is closely bound to the notion of movement, with kinetic energy: "It creates motion or results from motion; it means a process in which the dynamic level is just one variable, and by no means a constant." 9)

Rhythmic energy has continued to play a central role in Taylor's solo music in the intervening years - to be sure, in a way quite different from its role in the Unit. For although the Unit generally works with a drummer, who provides a more or less regular pulse, in Taylor's solo music, pulsed rhythms play a fully insubordinate role. If the appropriate metaphor for the Unit is that of an athlete "running an obstacle course where the hurdles have been placed at irregular distances", 10) the image that comes to mind for the solo work, if one is needed, is that of a sprinter, who, in a fully unpredictable manner, moves forward while constantly changing his pace; he hesitates, he stops, then once again dashes ahead. One finds in this music extremely dense and thereby static textures, where temporal demarcation of any kind seem not to exist; continuous motor rhythms, on the other hand, are found hardly at all. Whenever regular series of impulses do appear, they're constantly interrupted by irregular accents (e.g. by clusters in the bottom register), so that any sense of uniformity is obscured. The kinetic energy driving the musical whole results above all from the temporal arrangement of the accents, that is, from the coordination of time and intensity.

Since the late sixties, tonality in Taylor's piano music takes a variety of different forms. If the tonal substance on recordings like Unit Structures or Conquistador limits itself to a circling around tonal centers with comparatively weak gravitational force, tonal references in his solo recordings are far more plentiful and varied; they range from strictly atonal cluster-playing, to a kind of extended tonality involving motivic cells, and reach all the way to structures based on functional chord-changes, the likes of which would have been unthinkable in the Sturm und Drang period of the late sixties. In his work with tonal centers (not to be confused with keys), Taylor clearly favours reference points hostile to wind-players: A, E, B and F#. Chord changes, in the traditional sense, appear in Taylor's piano music relatively late, usually in ballads or lyrical pieces that thoroughly contradict the "wild man" image of Taylor propagated throughout the years. One of the first examples of his lyrical style is found in the extended solo introduction to Spring of 2 Blue Js, recorded in New York's Town Hall in November 1973. Further examples are to be heard in the selection After All on the LP Silent Tongues (1974) and Pemmican on Garden (1981). Common to all three pieces is a descending chromatic bass-line (in Spring and Pemmican, from B; and in After All, from E), over which is erected a harmonically functional sequence of chords - in Pemmican, for example: Bm - F# - Am - G# dim - G - G# - A, and so forth. This formula is hardly original; on the contrary, ever since Chopin's E minor Prelude, it has been a solid staple of romantic piano music; later, in the pop music of this century, it degenerated into a sentimental cliché. Why then does Cecil Taylor choose to revive, of all things, this hackneyed device, and further, what does he do with it? Motivational research falls outside the domain of jazz scholarship, so the "why" in all this remains open, but possibly part of the answer lies in the "how." Even if these chromatic passages are unmistakably romantic in tone, there's not the slightest trace of banality or of emotional indulgence in them. The model itself, burdened with history, doesn't induce Taylor, for example, to outdo anything or anybody; he could have, for example, taken the model's already built-in tendency towards sentimentality and intensified it. Instead, he treats it as matière pure, and transforms it into an authentic Taylor piece. This is achieved by first setting up a song-like, melodic world determined by the model's harmonic scaffolding; into this tranquil setting Taylor then injects tonality-wrenching bass-interruptions, arpeggios, and clusters. The chromatic rubato-ballads are thus simultaneously "in and out", and therein lies a great deal of their excitement.

It could be that Taylor eventually began to be wary of his kinship with Chopin, because on the LP For Olim (1986), in "Mirror and Water gazing", there appears a new ballad-type. Here one can also detect implied changes; the essential characteristic, however, lies in the refined blending of composition and improvisation; by virtue of an enormously differentiated touch-technique, this type of piece is considerably nearer in spirit to Taylor's "everyday" musical language than to the ballads fitting the Chopin-syndrome, which seem, above all, to mark the boundary areas of the lyrical style.

The repertory of Taylor's "everyday" style-purveyors is large, yet specific. Clusters of ever, possible kind continue to play an important role as they have always done, but for some time now they no longer occupy a central position:

- short, cluster-accents encompassing a wide registrar span; played with the forearm, the elbows or the hands.

- mobile-clusters; of narrow compass, these are hammered out at dizzying speed with two or three fingers; because of the great density of activity thus created, their effect is that of a flowing (or flying) stream of sound without identifiable pitches.

- static clusters; these are usually powerful masses of sound sustained with the help of the pedal; they appear relatively late in Taylor's work, assuming a generative role only in the mid 1980's.

- cluster-tremolos; their most frequent function is to demarcate large-scale formal divisions; in effect they say: "something new is coming", or "now the music is going to turn back to ..."

On the whole, one can notice that the application of cluster-techniques in Taylor's solo work shows a decreasing tendency, something not typical of his work with the Unit. And while clusters are still the dominant focus of the LP Praxis (1968), a far greater range of musical materials is to be heard as early as Indent (1973). The concentration of cluster-playing continues to decrease in subsequent records; moreover, the emphasis is placed increasingly on the mobile-cluster technique, a device that, as will be seen later, often serves to delineate what we shall term the "Area" sections of a piece's development.

A further salient characteristic of Taylor's piano music is the use of short bass figures that from time to time mark or at least hint at a tonal center. Such figures frequently involve a grouping of minor seconds (in Air Above Mountains: Bb - B - Gb - F; or: B - C - A - Ab), and often serve as motivic cells, or as stimuli for motivic development. Taylor uses chromatic bass-lines, on the other hand, usually as a foil to mobile-clusters in the upper registers.

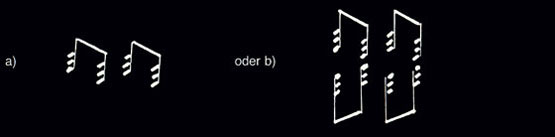

Another stylistic device, one which turns up in almost every recording, is a motive consisting of two chords moving in parallel or in counter motion. When two hands are involved, each hand mirrors the other, as the following diagram attempts to clarify.

Such chordal motives, which incidentally almost always have a downward contour, are often approached, as if being honed into, by upward-directed figures arising from the bass; the chordal motifs themselves, on the other hand, often lead into a falling bass figure - a constellation that serves to introduce some degree of relaxation in a piano style generally frought with tension.

Starting with Garden (1981) Taylor introduces an extremely original new variant of what is called in traditional jazz "the locked hands style"; a technique obviously intended to imitate the saxophone writing of the big band era, this was made famous by the pianists Milt Buckner and George Shearing, and in essence consists of using both hands to play a harmonically thickened version of a composed or improvised melody. Cecil Taylor relieves the procedure of its chordal framework and also eliminates its relaxed swing-character, considered indispensable by the style's original proponents. What remains is a synchronised movement of the two hands in parallel or contrary motion, executed with great agility and speed. Taylor uses the locked-hands technique to create short phrases, sometimes condensed to only one or two seconds, whose overall musical result is a high degree of motivic saturation, rhythmic terseness, and above all, immense drive.

Taylor also employs techniques of quite general application that are not tied to specific musical contexts, for example: sequence, call-and-response, stratification and motivic development.

Sequence, the repetition of a musical idea at a higher or lower pitch-level, is a compositional device equally relevant to both written and improvised music. With Taylor, sequences become a shaping force starting, at the latest, with Indent (1973). The technique of call-and-response, or antiphony, is also common to both written and improvised music, and can be found with great abundance throughout the Taylor discography. The procedure appears in almost every thinkable constellation; particularly frequent, however, is the situation, alluded to previously, where a sharply-accented staccato figure in the bass, sometimes substituted by a chordal motive, alternates antiphonally with mobile-clusters; countless other combinations, formed from widely varying materials, are of course possible.

Closely related to call-and-response patterns is the technique of stratification, or layering; in some sense, this can be thought of as a temporal variant of the call-and-response idea: In stratification, the "call" and the "response" simply occur simultaneously instead of separately. Taylor uses the procedure with far less frequency than antiphonal techniques, but when he does use it, he does so to great effect. A characteristic example can be heard in the title "Living" on For Olim; here the left hand plays a sharply-accented chromatic bass line; as a counterpoint to this, the right-hand superimposed " roaring " glissandi.

Motivic development also represents a structural principle of fundamental importance in Taylor's piano music. In general, Taylor's approach to improvisation has nothing to do with the "fantasizing" in romantic music; it also has nothing to do with an unconscious outpouring of feeling or with showy, mere emotion-laden displays of power.

What Taylor's approach does have to do with, and this is at first easy to overlook because of the high-energy dynamic, is the ability to think structurally at great speed; this, along with a kind of spontaneous constructionism that occurs as the music unfolds in real time comprise the real foundation of Taylor's music. The most bearable expression of all this is a specific process for developing motives that was already at work in his music of the 1960's. Unlike the approach of Ornette Coleman, whose chain-like motivic series 11) are quite freely assembled, Taylor's method clearly leans more towards systematic procedures. There's nothing casual about Taylor's motivic associations; he doesn't merely present ideas - he develops them; a motive, a thought, a structure, a way of moving is stated, stabilised by repetition, then spun out through variation; finally it is dissolved, whereupon the old idea is replaced by a new one, and the whole cycle begins anew. The motivic material that sets such processes in motion is not limited to a particular type of idea; Taylor sometimes uses a small cell that expands, gathers complexity and then splits; the chordal motives mentioned before can serve equally well as a starting point, as could a call and-response structure. In actuality, however, this last possibility is Taylor's preferred source; in the course of treating the two antiphonal elements, each can serve as a point of reference for varying the other, as shown in the following diagram:

a-b-a'-b-a"-b-a"-b'-a-b'-a'-b"-c-c'-c-c" etc.

Outlined here is a motivic principle dating back to a process developed by Taylor for the "Plain" section of Unit Structures (1966). There, "predetermined structures are stated, juxtaposed and reshaped in the process of improvisation." Or in the words of Taylor "content, quality and change grow in addition to direction found." 12)

The models for the ensemble work in Unit Structures also appear in Taylor's solo music, in connection with the overall form, i.e. with the organization of extended improvisational processes. To be sure, this is not always the case: the majority of Taylor's solo recordings, particularly of the early ones, are rather formless in effect. What's often involved here is a kind of stream-of-consciousness playing, where ideas freely associate with one another; the extremely high density of events, without recognisable formal divisions, or anything resembling goal-directed development adds to the overall feeling of uniformity. Examples of this kind of "formlessness" are found in the LP's Praxis (1968) and - for wide stretches - in Silent Tongues (1974). Lest there be a misunderstanding: these recordings reveal in part a very clear differentiation at the level of surface detail; at the macro-level, however, they are thoroughly uniform and one-dimensional. The image of a rasp may prove helpful: It's finely and precisely structured in one sense, yet in another, completely homogeneous.

Large-scale formal processes that follow the Unit Structures model appear incipiently in Spring of 2 Blue Js, more conspicuously in Indent. Of special significance are the techniques used to demarcate sectional divisions in the Plain and Area portions of Unit Structures: in Plain, "predetermined structures are stated, juxtaposed, and reshaped in the process of improvisation"; in Area, "intuition and given material mix in group interaction," to form "an unknown totality, made whole thru self-analysis (improvisation), the conscious manipulation of known material".13) On Indent (Side-A), this process materialises as follows: in Plain (ca. 7'00"), different structural units are manipulated successively; in Area, a one-dimensional and uniform texture of great density unfolds; the defining element here is the mobile-cluster technique, sporadically interspersed with sharply accented staccato figures in the bass.

Positioned between the extremes of a predominantly uniform and dense playing style as found on the LP Praxis, and a clearly demarcate formal layout such as on Indent, are found numerous intermediate stages. The most common and far-reaching principle determinate of such stages is that of simple succession; that is, the assembling of ideas of more or less contrasting character, and also of more or less broad dimensions, into a series directed by Taylor's flow of ideas: ABCDE... Repetitions in this context are avoided. On the other hand, there is also no overall goal-directed dramaturgy; the music is not led to high points and no large-scale formal connections are projected: the music doesn't go anywhere; it is there formal, in every second of its sounding.

The recordings that arose out of Cecil Taylor's solo work between 1968 and 1986 are not characterized by an overriding stylistic unity; instead, they represent steps in a non-linear evolutionary process, one not without its detours. Although a given stage doesn't proceed neatly from its predecessor, there is, however, an observable inner consistency involved, due to the influence of work and experience. The following short sketch of the eight solo recordings I have had access to should not be misunderstood as an "up tempo" critique; my goal is simply to depict broadly those characteristics relevant to the evolutionary processes under discussion.

Praxis

Emphasizes clusters; high density of events throughout, use of contrasting foreground details; flowing, uniform macro-form; high energy playing.

Indent

Greater multiplicity of material and structural differentiation, more linear playing than clusters; systematic use of variation-principle; clear formal divisions.

Solos

Conceptually similar to Indent; relatively high proportion of tonal material.

Spring of 2 Blue Js

First appearance of the romantic "chromatic" Ballads (Chopin-Syndrome); more strongly differentiated touch-technique; colouristic function of pedaling.

Silent Tongues

Primarily tour de force with an immensely high density of events. Exception: "After All" (Chromatic Ballad).

Air Above Mountains

Clear juxtaposition of Plain (motivic work) and Area (uniform texture, mobile clusters). This last aspect is accorded more time and also has a greater impact.

Garden

Structurally closed passages are more extended than usual; material is carefully developed, at a gradual and relaxed pace. Less emphasis on mobile-cluster formations. Marked tendency towards an economy of means. Generally more accessible to the listener, although not less complex.

For Olim

Clear increase of structural and timbral variety. For the first time, more frequent use of demarcating materials; work with tone colour plays an essential role; the parts selected to serve as "pieces" display an independence of character and mood; the significance of clusters is further reduced. Mobile-clusters are deployed judiciously, and in part programatically (in "For the Rabbit", for example). With "Mirror and Water Gazing" and "The Question", there appears a new type of Ballad. Generally speaking, the album can be seen as the beginning of a new stage in Taylor's solo work.

The Unit

The name chosen by Cecil Taylor to denote the groups led by him is Unit, a term whose appropriateness in a social context so dominated by financial and other uncertainties is surely not always easily justified.

Over the years, the Unit has undergone a series of personnel changes that left their traces on the group's music. At least through the late 1970's, however, it is legitimate to speak of a more or less stable group identity, to some extent influenced by the particular musicians playing with it at a particular time, but one that nonetheless is continuous over a period of many years.

The alto saxophonist Jimmy Lyons, who died on May 19, 1986 at the age of only fifty-three, had belonged to the group for many years. A consummate soloist, he was also Taylor's closest and most trusted friend, the two having experienced both the years of struggle and the period of growing success together. "All the music that I write will always be dedicated to Jimmy Lyons," Taylor stated in a 1988 interview, continuing: "..he was in many ways my protector, as well as the most reliable, devoted musician I've ever worked with." 14)

In writing about Unit Structures a couple of years ago, I described Lyons' stylistic approach as follows: "Lyons is something of an outsider in free jazz, because his playing usually sounds like c successful transformation of Charlie Parker's musical idiom into a new context. While taking full advantage of the freedom Taylor's music offers him, Lyons achieves a rhythmic and melodic continuity typical of bebop musicians." 15) This characterization continues to apply throughout the 1960's and beyond. One modification is necessary, however: as Taylor's music placed progressively more and more emphasis on energy-oriented playing, Lyons' style was not unaffected screeching in the high-register, multiphonics, a-melodic sheets of sound - these all became a part of Lyons' vocabulary. In the end, Lyon's mastery of both the linear-melodic and the energy oriented styles, along with his ability to employ each purposely as context required, made Lyons the ideal partner for Taylor. One should add that, even in the intensest moments, Lyons was capable of maintaining, to a remarkable extent and with great authority, a clear sense of linearity in his approach.

In comparison with Lyons, other wind players with whom Taylor has collaborated since the late 1960's cut somehow pale figures on their recordings with the Unit. Sam Rivers, whom Taylor hired in 1969 for one of the group's European tours, plays mostly under his level on the 3-LP set recorded at St. Paul de Vence in France; restricting himself to an energy-oriented style, something untypical for him, Rivers never fully gets a grip on the Unit's thematic material. As for the contribution of the tenor player David Ware, who worked with the Unit in 1976-77 and can be heard on the album Dark to Themselves, recorded in Ljubljana, like Rivers, he too relies quite one-sidedly on an aesthetic dominated by overblowing and screeching; his function within the group thus resembles that of Rivers, as possibly was Taylor's intention.

The trumpet player Raphé Malik occupies an exceptional and strange position within the Unit's development. Malik became acquainted with Taylor while studying literature at Antioch College, and after participating in the workshop led there by Taylor, he played sporadically with groups headed by Jimmy Lyons; in 1976 he joined the Unit, where he remained for two years, until 1978. He nevertheless appeared on a total of seven LP's, among which is the 3-LP set recorded in 1978 at the Liederhalle in Stuttgart, One too many sailty swift and not goodbye. Malik's playing on these records proves him to be a weak improviser; to be sure, he knows the thematic material of the Unit in depth, and thereby compensates somewhat for his technical and musical deficiencies; his reliability enables him to keep his bearings within Taylor's labyrinthine catalogue of basic structures, but his improvisations reveal an inflexible, tin-like sound, as well as a tendency to produce brief, code-like melodic fragments; his playing thus seems to be short-winded both in the literal sense and in the figurative one that he cannot sustain a flow of ideas.

In 1987, the alto saxophonist and flutist Carlos Ward assumed the difficult role of "successor" to Jimmy Lyons. Ward, an experienced participant in the free jazz scene, had for years been a member of Abdullah Ibrahim's group, and had also performed with musicians such as Karl Berger, Don Cherry, John Coltrane, Sunny Murray and Carla Bley. Like Lyons before him, Ward is primarily a "linear" player whose strength lies in a melodically clear style, one rich with motivic life. At the same time, he plays more "tonally" than Lyons; within a basic framework consisting of riff-like repetitions and motivic variations, he occasionally permits the appearance of modal references, tonal connections (G-minor) or Blues phrasings. That it is not always easy for him to play authoritatively within the group's power-play style probably has less to do with him than with the group's inter-personal dynamics (more on this at a later point).

Frankly, I cannot infer what reasons led Cecil Taylor in 1975 to accept the Egyptian violinist Ramsey Ameen into the Unit. That the violin, by its very nature, would pose acoustical difficulties for even the best of violinists attempting to make himself heard in the high-energy context of the Unit is clear, but that's not my problem with Ameen (who, as he puts it, disdains "fashionable electric pick-ups"). My problem with Ameen is that his musical qualities put me at a loss for words. Inspired by a music-loving father to take up the violin, later scolded by his teacher for his preference for jazz, Ameen finally set out on the path to free jazz, taking Ornette Coleman as his model. His improvisations cause one to feel the lack of practically everything improvisation should mean in such distinguished company: secure intonation, rhythmic fire, authority, ideas...

The jazz credentials of the violinist Leroy Jenkins, who took over Ameen's place in 1987 in connection with a European tour of the Unit, are by and large uncontroversial - a fact that unfortunately doesn't diminish the dubiousness of his contribution to the Unit's music.

Also problematic is the function within the Unit of the contrabass. Difficulties are posed here not only by Taylor's persistent use of all registers in his playing, but also by his preference for extremely "dynamic" drummers - two factors that at times seem to make the inclusion of a bassist in the group superfluous. That the Unit has in fact dispensed with bassists during some phases (and this applies for a whole series of recordings) therefore comes as no surprise. The bassists who can meet the challenges presented by Taylor's high-energy approach are always exceptionally strong and energetic "workers": Alan Silva in the 60's, Sirone (Norris Jones) during the 70's and William Parker since the early 80's; at least so far as the Unit is concerned, these are all players for whom the main issue is not timbral subtlety or virtuosity in the upper register, but rather the creation of a solid, at the same time driving, rhythmic basis. The two-hour improvisation One too many... brings home just how authoritatively Sirone is able to succeed at this; in this marathon-set, where even so powerful a drummer as Ronald Shannon Jackson repeatedly cannot keep up, Sirone's expenditure of energy simply stretches credulity.

The collaborative relationship between Cecil Taylor and his drummers defines one of the most sensitive aspects of the group's communicative dynamics. More is required from one of the Unit's drummers than merely "getting the mail off in time" and supplying sufficient drive and energy. The percussive character of Taylor's quite specific rhythmic sensibilities demands from a drummer both constant preparedness for interaction, as well as a certain lightness appropriate to Taylor's sometimes dance-like sense of gesture. In my estimation, only two percussionists meet these demands unqualifiedly: Sunny Murray, who collaborated with Taylor in the period 1959-64, and Andrew Cyrille, who played with the Unit from 1964-75, enjoying a respect within the group comparable to that accorded Jimmy Lyons' (and this was not just due to the longevity of his association). Both Sunny Murray and Andrew Cyrille are extraordinarily "melodic" drummers who both know how to make their instruments sing; their approach, even when extremely loud and powerful, always possesses great mobility and lightness, qualities meshing unusually well with Taylor's rhythmic style.

The successor closest in spirit to Cyrille's conception was Mark Edwards, who worked with the Unit in 1976; he can be heard on the album Dark to Themselves; furthest away is Ronald Shannon Jackson, a member of the Unit from 1978-79. Jackson's rock-inspired aesthetic, developed while playing with Ornette Coleman's electric band Prime Time, offers a resistant counterpoint to Taylor's music, and in many regards, steers the group in a radically different direction than that indicated by his predecessors. Befitting a rock-oriented approach to sonority, Jackson plays a relatively bright and crisply-voiced drum-set; his overall style is heavier than normal, and, in relation to Taylor's playing, the musical result is more oppositional than integrative and supportive. For example, Jackson will sometimes inject metronomically regular accents into a rhythmically free passage, literally thundering them out on the bass drum and snare; or, in the course of a powerful build-up of tension, he might try to set up a funk beat; similarly, at that very moment where fragile articulative structures are beginning to unfold, he might introduce a familiar "hit all the tom-toms" flourish borrowed from jazz-rock. One can assume that Cecil Taylor appreciates Jackson's controversial style because it adds an intentionally contrastive element to the group's identity without unduly threatening its stability. Taylor himself, it should be observed, practically never gets involved with Jackson's interventions; moreover, his refusal to do so occasionally creates the effect of an intentionally rejected attempt at communication. A related phenomenon, one that is particularly obtrusive in the 1978 Stuttgart concert (One too many..), is Jackson's constant dropping in and out of the music; there is no bearable justification for this, and what's even more irritating is that it seems to exert no palpable influence on the actions of the other musicians.

Considerably more integrated into the Unit's music is the drumming style of Rashid Bakr, with whom Taylor worked in the period 1981-84. With regard to sonority, Bakr is rather non-assertive; in pulse-free passages (as on Calling it the 8th), he tends towards a manner of playing that's part colouristic, part conversational; he is however also fully capable of playing convincingly in driving, high-energy contexts.

Thurman Barker, for some time now the last in the lineage of Unit drummers, comes out of the Chicago AACM circle; having collaborated with Anthony Braxton, Joseph Jarman and Muhal Richard Abrams, his work with the Unit is documented on two LP's arising out of a European tour in November 1987: Live in Bologna and Live in Vienna. Barker is a versatile, sonority-sensitive musician; he's not primarily a forceful energy player; on the other hand, he is a cooperative, communicative ensemble-player, with a marked tendency towards (implied) time-playing.

Without doubt, the dominant role in the Unit is played by Cecil Taylor himself; Taylor's influence as "bandleader" extends not only to the choice of thematic material and to any adjustments in the group's underlying conception, but also, and most importantly, is felt in all matters concerning Taylor's own activities as a piece develops. Taylor plays almost always, and by doing so, determines the musical action to a far greater extent than any other Unit musician. On this point, it is absolutely incorrect to assert, as one sometimes reads, that his playing with the group in no way differs from his unaccompanied work. Certainly there are many correspondences, especially between the unaccompanied playing and his solos with the Unit. On the other hand, there exist very substantial differences between his unaccompanied playing and his ensemble playing. The most important of these lies in the rhythmic domain: While his solo piano performances are for the most part rhythmically free, in a rubato-tempo, interspersed with numerous fermati, and essentially without pulse, his ensemble style, particularly during the Area-complexes, is almost always very pulse-oriented, and remains so, in fact, even when the time-keeping drummer drops out. Taylor's Unit playing is also generally less tonal than his unaccompanied work. Particularly when he's not taking a solo, but "comping" concept that of course really doesn't apply), Taylor tends to use clusters far more than he does in his unaccompanied music; when playing with the group, he tends to focus more on sound and rhythm, and less on motivic work. Finally, one should mention differences in the two approaches to dynamics: In the unaccompanied recordings, there is a carefully modulated continuum of shadings and gradations linking pianissimo and fortissimo; in the Unit, the dynamics are generally set to maintain the highest possible level of intensity throughout.

Taylor's manner of "comping" drew reproach from jazz critics as early as the 1960's. Whitney Balliett, who had otherwise given Taylor's music favourable notice from the very beginnings, even wondered why Taylor bothered to play with other musicians at all, since as a rule his accompaniments were nothing more than extensions of his solos. 16) Doubtlessly there is something to this view, for even if the tonal and motivic substance of Taylor's solos does differ from that of his accompanying style, both are still marked by a heightened activity level so characteristic of Taylor's music. To be sure, there is no question in anybody's mind that Taylor does not "comp" in a traditional sense. He doesn't step back, for example, and supply his wind players or violinists - with the traditional rhythmic carpet from which they can "take off". On the contrary, he engages them in a permanent dialogue, provides them with kinetic energy, drives them forward - an approach that undeniably sits less well with less skilful improvisers, more than one of whom has been derailed by it.

Over the past twenty years, the Cecil Taylor Unit has produced eleven albums (including several 2-LP or 3-LP sets) - hardly a great many for a group of this renown world-wide. With two exceptions, all of these represent live recordings of concerts given in the U. S. (2) and in Europe (7), and thus to some degree reflect the group's everyday, on-the-road reality. The two studio recordings, The World of Cecil Taylor and 3 Phasis, were produced for the prestigious "Recorded Anthology of American Music"; financed by the Rockefeller Foundation, this extensive recorded documentation includes practically every musical statement ever uttered on the entire North American continent, from New England hymns, to early Blues, to music by Cowell, Ives and Cage. One possible influence this noble environment may have had on the Unit's music will be discussed later.

The Unit's Style

In the Unit's recordings, just as in Taylor's solo recordings, there appear both a number of stylistic constants, as well as several variables influenced by context and evolution. Among the constants are: first, a specific type of thematic and formal organisation; second, the concentration on a particular tonality and on a particular tempo.

As a rule, the Unit's thematic and formal strategies derive from the Unit Structures-model: an Anacrusis section, generally a piano introduction with typically Taylor-like bass patterns, begins a piece; then comes a Plain section, where thematic-motivic material is presented, usually by two winds, playing more or less in unison. Exactly how much of this is in actual unison is subject to wide deviations; with the 1968 line-up, for example, the alto and tenor are so seldom synchronous that these passages should really be classified as a kind of heterophony. Whether or not this situation results from a conscious decision, or from River's less than perfect familiarity with the material, is open to question.

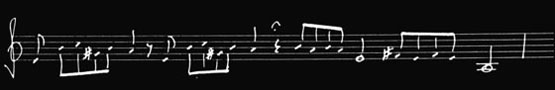

As was already the case by Unit Structures, the thematic material used by Taylor's group usually consists of short melodic phrases presented quite straightforwardly in continuous eighth- or; quarter-notes. These phrases are frequently divisible into two halves, defined by repetition or sequencing, and are also clearly tonal, as in the following excerpt taken from the LP Cecil Taylor; here the key is A-minor:

One should note that such materials are never conceived as independent entities, as is generally the case, for instance, with bebop themes or with those of Ornette Coleman; instead, it is assumed that they will be transformed through improvised interpolations and interruptions, typically supplied by Taylor, for example, as comments on the motifs played by the unison winds. One often has the impression in such contexts that Taylor is playing against the other musicians, so as to create contrasting layers within a heterogeneous whole. Not infrequently the winds also begin to improvise between the music's fixed portions, thereby weakening the given material's unifying influence even further; the musical result of all this is a kind of miniature chain-form, similar to those encountered in Taylor's solo work.

As for tonality and tempo, the conclusions one is led to draw here are

a bit disconcerting. If one plays through all of the Unit's recordings

more or less at a single sitting - admittedly an unreasonable act - and

listens analytically, then two things become clear. First, almost all

of the thematic-motivic materials are circling around the tonal centers

of B. E or F#; for long stretches, this also applies to Taylor's supportive

playing during other musicians' solos (and therefore to the solos themselves);

and also to the fixed materials with modal or key-like qualities (mostly

in minor). As for tempo: Whenever the rubato phase of the Plain section

has ended and the pulsed rhythms typical of the Area section begin to

be established, the odds are great that these will assume a tempo of ![]() = 350, with occasional deviations in the range

= 350, with occasional deviations in the range ![]() = 320-390. In other words, after a certain point in a piece's development,

the Unit's music will automatically shift to a very fast tempo, moreover,

one whose speed remains constant throughout a whole piece.

= 320-390. In other words, after a certain point in a piece's development,

the Unit's music will automatically shift to a very fast tempo, moreover,

one whose speed remains constant throughout a whole piece.

A standardized tonal center around B and a standardized pulse of ![]() = 350? To what can one attribute such uniformities? Allow for some speculation.

The invariant circling around B. with a marked tendency towards B-minor,

was mentioned earlier, in reference to Taylor's solo work, and surely

part of what's involved here with the Unit is that Taylor has simply transferred

certain structural idiosyncrasies of his solo music to the group context.

But is the E - B - F# centricity conscious or unconscious? Is it perhaps

useful in extirpating from the wind players' vocabularies all those flat-key

clichés lying so easily under the fingers? Or is it nothing more

than a kind of habit?

= 350? To what can one attribute such uniformities? Allow for some speculation.

The invariant circling around B. with a marked tendency towards B-minor,

was mentioned earlier, in reference to Taylor's solo work, and surely

part of what's involved here with the Unit is that Taylor has simply transferred

certain structural idiosyncrasies of his solo music to the group context.

But is the E - B - F# centricity conscious or unconscious? Is it perhaps

useful in extirpating from the wind players' vocabularies all those flat-key

clichés lying so easily under the fingers? Or is it nothing more

than a kind of habit?

The revelation that the Unit's heart ticks at a constant rate of about 350 times, a minute, frankly speaking, irritated me. Didn't I read something somewhere - or even write something - about that? "This means a measure of four quarters approximately corresponds to the human pulse; furthermore, it also signifies that the kind of free jazz under discussion is perhaps more closely bound to body-rhythms than has been commonly assumed." 17) If what I wrote here in 1978 about "Euro-Time" is indeed true, than the New York heart-beat apparently is considerably faster than that in Berlin or Wuppertal. But does all this really have anything to do with physiological constants, set unreflectively to music? Could it not involve a musical principle, motivated by a conscious aesthetic?

The Unit's Evolution

My attempt here to reconstruct a twenty year evolutionary process on the basis of 11 records is surely not unproblematic, especially because these recordings appear at unequal intervals, sometimes with gaps of several years; at times these gaps signify periods of inactivity; but they also cover periods where the Unit was working, but not recording. In any event: changes in the Unit's expressive vocabulary and in its ensemble style are indeed observable over these twenty years; they do not follow one another in a logical sequence, however; instead, they tend to evolve in a series of pendulum-swings between different expressive and structural approaches.

Originally appearing under the title Nuits de la Fondation Maeght

on the Shandar label, and then later as The Great Concert, on Prestige,

the live concert recording made at St. Paul de Vence in July 1969 contains

some extraordinary high-energy ensemble music, but because of the persistently

high density of sound and activity ( ![]() = 380), the overall effect is uniform and rather unstructured. Sam Rivers

has trouble here playing authoritatively amidst the vehement outbursts

of Taylor and Cyrille; Jimmy Lyons, in contrast, uses those outbursts

to inspire an extended solo of great melodic clarity and rhythmic intensity

- in my opinion the concert's high point. Incident tally, this is the

first instance where Taylor uses one of his "Indian chants" as a warm-up;

much later, in the 1980's, chanting develops into the Unit's obligatory

opening ritual.

= 380), the overall effect is uniform and rather unstructured. Sam Rivers

has trouble here playing authoritatively amidst the vehement outbursts

of Taylor and Cyrille; Jimmy Lyons, in contrast, uses those outbursts

to inspire an extended solo of great melodic clarity and rhythmic intensity

- in my opinion the concert's high point. Incident tally, this is the

first instance where Taylor uses one of his "Indian chants" as a warm-up;

much later, in the 1980's, chanting develops into the Unit's obligatory

opening ritual.

The LP appearing four years later, Spring of 2 Blue Js (the A-side, already described, contains a piano solo) is more differentiated in its structural layout and as a whole, more listenable than the St. Paul de Vence recording. Appearing with Taylor in this quartet version of the Unit are Lyons, Sirone and Cyrille. Even within moments of peak energy-playing, the music here reveals a very intense rhythmic interaction. Particularly impressive is an emotional crescendo that builds for over ten minutes, somehow creating the illusion that the music is becoming constantly higher, faster, and louder, although objectively this is not the case. Equally exciting is a quite short (unfortunately) bass/drum duet (without Taylor!); the feeling here is comparatively relaxed, a clear contrast to the records prevailing mood of extreme tension. Like most of the Unit's "pieces", Spring of 2 Blue Js has an ending, which in reality is not an ending at all: the piece merely fades out uneventfully.

Dark to Themselves, recorded in June 1976 in Ljubljana, is similar in layout to Spring of 2 Blue Js. It acquires its own sound primarily because of the different personnel involved. For the first time; Raphé Malik and David Ware are performing; in the place of Andrew Cyrille is heard Mark Edwards, playing very sensitively, with a marked sense for dynamic gradations. Jimmy Lyons once again proves an outstanding soloist; here he concentrates on motivic chain-associations, in the course of which he constantly refers back to the basic thematic material.

All three recordings discussed above follow the Unit Structures model: Invariably the Plain-sections, each lasting somewhere between five and seven minutes, lead into the Area-complexes, featuring the soloists. Two weighty exceptions are found in the Unit's contributions to the "Recorded Anthology of American Music" on New World Records, Cecil Taylor and 3 Phasis; here there is such an unusually dense proliferation of fixed thematic materials that the overall effect approaches that of an extended Plain-complex. For long stretches, the two wind players, Raphé Malik and Jimmy Lyons assume the role of mere presenters of pre-composed ideas drawn from a truly gigantic catalogue of motifs; at more or less regular intervals, they inject portions of this material into the trio improvisations by Taylor, Sirone and Jackson. The compositional scaffolding is thus assigned a far greater significance here than in any other Unit recording. One possible explanation for this lies in the recordings' having been made, quite atypically, in a studio; these are in fact the Unit's only studio recordings; but surely another influence is that the Anthology's background cultural politics may have simply whetted Taylor's compositional appetites.

Be all this as it may, I am frankly unable to infer what compelled Gary Giddins to rank these recordings with the legendary Blue Note LPs from 1966, Conquistador and Unit Structures.18) Quite apart from the more convincing solos, and above all, superior rhythmic substance on both Blue Note records, the older recordings also reveal a far greater degree of integrity and inner consistency in their conceptual and formal layout. Parts of the New World productions appear quite confused.

In June of the same year as the Anthology recordings, there appeared two albums made from live concerts given within a two-day period in the Black Forest town of Kirchzarten, and at the Liederhalle in Stuttgart. The differences between the two could scarcely be greater; that the Unit's playing can undergo such radical changes within such a short period is revealing commentary on the group's underlying concept. Live in the Black Forest is a set of pieces constructed according to the Unit Structures-model, with relatively succinct developmental processes and a comparatively large variety of formal and expressive devices. In the appearance at the Stuttgart Liederhalle, the Unit abstains from using the structural build-up associated with the Plain-complex. Instead, within an extended free improvisation that lasts almost for two hours, they introduce two lyrical rubato-ballades in the minor-mode. The recording is unusual, not only for its temporal proportions, but because of striking discrepancies in the disposition of playing forces: During these two hours, Cecil Taylor always plays; Jimmy Lyons is heard for 18 minutes; Raphé Malik plays for only 8 minutes. (What is he doing during the rest of the time?) If such calculations seem a bit petty, they nevertheless say quite a bit about the group's interpersonal dynamics. To put it mildly, balance does not seem to be the main consideration here.

Two Unit records of greater stylistic consistency than those discussed so far are: It is in the Brewing Luminous, recorded in February 1980 during an engagement of several days at the New York club, "Fat Tuesday", and Calling it the 8th, a concert recording from the Freiburg Jazz Days festival in November 1981. Brewing Luminous is predominantly a thematic (at best some weak references to material from the Unit Structures-model can be heard) and profits from the distinguished, quasi "retrospective" line up of personnel: Alan Silva on contrabass, plus Sunny Murray and Jerome Cooper on drums. The obvious misgiving that two drummers would lead to overly muddy textures and to a lack of rhythmic definition, turns out to be unfounded. Murray and Cooper interact with extreme precision, and the overall effect of the rhythmic foundation they provide is quite clear; although the feeling of pulse is substantially weaker than usual, their contribution even swings in a way unique to free jazz.

Particularly impressive is the improvisatory process retained on Side

C of the double-album. In an extended build-up lasting well over 12 minutes,

four diverging musical layers are overlapped to form a forward-driving

whole. The two drummers furnish the basic rhythmic groundwork and heightened

momentum by means of shuffle-like eighth-note triplets ( ![]() = 170), interspersed by off-beat accents hammered out on the drums; Alan

Silva creates a con arco tier of colour in the low register, to

which Ramsey Ameen adds contrast in the treble; simultaneously Taylor

unifies the various strands by playing mobile-clusters in all registers.

An exceedingly successful piece of time-anchored sound/energy music.

= 170), interspersed by off-beat accents hammered out on the drums; Alan

Silva creates a con arco tier of colour in the low register, to

which Ramsey Ameen adds contrast in the treble; simultaneously Taylor

unifies the various strands by playing mobile-clusters in all registers.

An exceedingly successful piece of time-anchored sound/energy music.

The LP Calling it the 8th documents the work of a quartet version of the Unit, to my taste one of the best heard since the 1960's. Jimmy Lyons, Cecil Taylor, William Parker and Rashid Bakr create a richly interactive music, one that alternates between an energy-oriented and a more relaxed style, between velocity playing and wide-intervalled paeans.

In the live recordings stemming from concerts in Bologna and Vienna on November 3 and 7 in 1987, the Unit Structures-model is finally discarded. The playing here is completely free: total improvisation, but not total communication. For while Cecil Taylor, apparently unmoved by events going on around him, concentrates predominantly on an extremely dense-style of energy-playing, Leroy Jenkins' and Carlos Ward's contributions never have a chance to gain a foothold, and are episodic in effect. Thurman Barkers marimbaphone introduces a new colour, pentatonic in hue and with a lightly exotic flair, which Carlos Ward takes up on the flute.

Cecil Taylor, Composer?

In his liner notes to the American release of the St. Paul de Vence concert, Gary Giddins asserts: "Cecil Taylor is fundamentally a composer."

In an interview with Meinrad Buholzer in 1984, Taylor declares: "I am not interested in compositions, in discipline, and all that academic stuff, where everything is determined. That's all prison cells." 19)

To the participants of a 1985 orchestra workshop in Banff, Canada, Taylor explains: "To sit down and write a piece of music and to ask musicians to perform that music under the same directorial tutelage that Händel gave his musicians, seems to me to be rather questionable in concept." 20)

In a 1987 conversation with Kenny Mathieson, Taylor says: "So I think composition - in quotes - is really more than anything else an archivist's nightmare. Because it does not have anything, or very little, to do with the contemporary spirit of musicians who want to create..we all realized a long time ago that music does not exist in the notes, it exists in one's internal cavity, one's body, or more sentimentally, perhaps, one's heart. Certainly in one's head. But the notes are only signs, communiques, to the thrust of the music." 21)

Cecil Taylor, Composer?

That the Unit works with predetermined materials cannot be doubted. Composed motivic material supplied by Taylor is especially important in the so-called Plain-sections of the Unit Structures-model. But composition also takes other forms in his work, for example: the "chromatic ballades" on his solo recordings; the song-like rubato themes on some of the recordings with the Unit. From the perspective of contemporary composition (in jazz as well as in serious music), Taylor's manner of composing has little in common, either in approach or end-results, with current developments. His music is, as it were, archaic, rudimentary. Consider: its short and florid motivic chains, played monophonically; its "songs" with functionally tonal references based on long-exhausted (chromatic) bass-lines; its relatively tightly circumscribed frames of reference; its lack of large-scale formal connections - all of this points quite clearly to a compositional method of remarkably reduced means.

But the perspective is false here, and Gary Giddins is wrong. For Cecil Taylor is by no stretch of the imagination "essentially a composer", and certainly not one whose work should be measured along side that of Anthony Braxton or Barry Guy and/or Pierre Boulez or György Ligeti. For inasmuch as Taylor furnishes his colleagues (or himself, for that matter) not with compositions in the traditional sense of permanently fixed musical configurations, but, on the contrary, provides them (and himself) with "processable" materials; and inasmuch as he doesn't give instructions, but makes suggestions and offers - then Cecil Taylor is clearly not a composer, but first and foremost, an improviser; similarly, the Unit is not a group of interpretive performers, but an improvisation ensemble. Drawing on the oral tradition of Afro-American music, Taylor makes his musical offers, not in writing, but by direct oral instruction. Working note by note, interval by interval, he imparts by talking, singing and playing to his musicians all of the musical information that will, when eventually put together, constitute a piece's thematic material.

This procedure, as just said, is not new, but is firmly rooted in the traditions of folk music; in jazz too, it has had its predecessors: Charles Mingus, for example. Cecil Taylor: "I had found out that you get more from the musicians if you teach them the tune by ear, if they have to listen for changes instead of reading them off the page, which again has something to do with the whole jazz tradition, with how the cats in New Orleans at the turn of the century made their tunes". 22) Taylor said this in the mid-1960's' when composition in his music still played a comparatively large role.

Listening to Taylor

"The intensity of Taylor's performances is taxing, intimidating - at times frightening," writes Mark Miller in 1986 in the Banff-Letters 23). In a 1987 Down Beat article, Kevin Whitehead remarks: "The problem with Cecil Taylor is not that he's hard to listen to, but that people find it hard to listen. You can't hear his music with half an ear - it requires attention, because he's made up his own rules." 24)

That Cecil Taylor's music poses listening demands far exceeding those usually required for jazz; appreciation can be observed by watching the audience at any of his concerts: there's no relaxed foot-tapping and finger-snapping; no one's leaning back peacefully in his chair, a dreamy smile on his lips. Cecil Taylor's music forces one to listen, to concentrate. Anyone properly attuned to those hours-long, energy-laden processes underlying his music at once experiences a powerful tension that later translates into psychological exhaustion. Being "wiped out" after one of his concerts is thus fully natural and proper; something is askew if one is not.

Valid as all this may be the emotive factor here is not the central one; we are, after all, discussing music, not sport, and let the point resound: It is a music of some scope and ambition. To the question, "Is your music about understanding, or about feeling?" Taylor replies: "Well, understanding. If the listener is in tune with his emotional make-up, then that includes understanding. I mean, the emotions inform the intellect - and not vice-versa." 25) Mind you, it is undoubtedly the case that an exclusively analytical approach to Taylor's music would prove less than successful. Surely if one went to the trouble of transcribing all of his recordings, and then analyzed the results in great detail, the conclusions drawn would be useful, but incomplete; admittedly one would learn a lot but not get all the way down to the music's inner core, its spiritual essence. Nevertheless, to maintain, as is commonly done, that in principle there's nothing to understand in this music, that one only has to surrender in order to experience it properly - this is fully untenable and absurd. If someone pokes you in the eye on a dark night, you'll see light; but surely you'd like to know who's doing the poking and why. Cecil Taylor is an intellectual musician, and therefore inquiring into how he achieves a particular musical effect is hardly irrelevant to appreciating his music; indeed, it can only increase one's enjoyment. Furthermore, the apprehension that his music's underlying constructive principles are far too complicated to be heard is thoroughly ungrounded. If anything and I hope this has come across in this text, such principles are rather easily grasped. Kevin Whitehead, in a review of For Olim, expressed this point succintly: "Taylor's working method is no secret; he often starts with a tiny kernel of musical information, expanding it and transforming it, distilling it into a new kernel and starting the process again: It's a simple process really - theme and variation, call and response - and once you know to listen for it, everything falls into place." 26)

With certainty, things are not always quite so simple, but in principle, Whitehead's comment does reveal several helpful keys for a cognizant, comprehending approach to Taylor's music, particularly to his solo music: variation, antiphony, motivic development. To be sure, the clarity of this formulation is obscured by the sheer density and speed with which Taylor's musical processes unfold. Taylor works with elements taken from a gigantic system of building blocks, which he again and again assembles in new ways. If occasionally one doesn't recognize this and/or cannot recognize this, then the problem probably lies in the end with these elements' enormously dense interior structures. Taylor is a systems-man, who conceals his system with speed.

Another aspect impeding a "cognitive" approach to Taylor's music should be seen against a backdrop of listening habits originally indigenous to European classical music, but which occasionally also play a significant role in jazz. The listener of classical music - and I mean the listener, not the consumer - expects that a piece will somehow "tell a story", in other words: that a succession of clearly differentiable musical events, each bearing to the other a definite relationship, will run their course with a certain regularity and logic; such a listener expects that connections of various sizes and shapes will be made, that there will be references to material already heard or to be heard later, that there will be a purposeful build-up of tension, or some other kind of goal-oriented musical process. Cecil Taylor's music - excluding the Plain-sections, with their diverse thematic references is obviously not narrative in these senses. The extreme energy- and density-levels in the Area-sections ultimately lead to a uniform and homogeneous musical result. A constantly turbulent texture tells no stories, creates no formal connections, refers neither to the past nor the future, but simply is: a motion-filled, tempestuous state, into which the listener must, as it were, dive headlong; one exposes oneself to such music, to be tossed back and forth without worrying about where and whither. Such an attitude towards listening is admittedly tinged with ritualistic traces, and the same can be said of the music that engenders it. Anyone who wishes to listen "cognitively" to this music, in the same way one listens to a Beethoven Sonata or one of Ben Webster's ballad-like discourses on love, will find himself hopelessly stranded; after a while the attention will wander, because all those richly charged moments will have unexpectedly changed into a monochrome grey. Of course if the emotions correctly inform the intellect, as Cecil Taylor demands, this can hardly occur.

Notes

- Ekkehard Jost: Free Jazz, Mainz 1975, 96.

- Nat Hentoff: The persistent challenge of Cecil Taylor, in: Down Beat 25. 2. 1965.

- Kevin Lynch: Cecil Taylor and the poetics of living, in: Down Beat 11/1986, 24.

- Meinrad Buholzer: Cecil Taylor (Interview), in: Cadence 12/1984, 5.

- Gudrun Endress: Cecil Taylor. Spielen, als ob es das letzte Mal wäre (Interview), in: Jazz Podium10/1984, 8.

- Lee Jeske: Percussive pianist meets melodic drummer, in: Down Beat, 4/1980, 17.

- Kenny Mathieson: striking the note, in: The Wire 46/47 (12/1987).

- Zit. quote from R. S. (Ramsey Ameen): Covertext Liner notes to New World Record NW 201.

- E.Jost: Free Jazz, Mainz 1975, 80.

- Ibid.84.

- Ibid.57.

- Ibid.89.

- Ibid.87.

- Zit. quote from Spencer A. Richards: Covertext liner notes to 'Live in Vienna' Leo records LR 408/409.

- E. Jost, Free Jazz, 90.

- Whitney Balliett: Such sweet thunder, London 1968, 236.

- Ekkehard Jost: Europäische Jazzavantgarde - Emanzipation wohin? in: For Example. Workshop Freie Musik 1969-1978, Berlin 1978, 58.

- Zit. quote from J.W., in: Jazzthetik 1/1988, 55.

- Meinrad Buholzer: Cecil Taylor, in: Cadence 12/1984, 9.

- Zit. quote from Mark Miller: Cecil Taylor. Musician, poet, dancer, in Coda 220 (6/1988), 5.

- Zit. quote from Mathieson, in: The Wire 46/49, 59.

- A. B. Spellman: Four lives in the bebop business, London 1967, 70.

- Zit. quote from M. Miller, a. a. O./op cit.

- Kevin Whitehead: For Olim (Rezension), in: Down Beat 11/1987, 30.

- Zit. quote from G. Endress, a. a. O./op cit., 7.

- K. Whitehead, a. a. O./op cit.

Translation: Daniel Werts